Two-thirds of Black women and more than half of Black men have been struck from jury service in Duval County death penalty cases, more than double the rate at which white prospective jurors are excluded, a study of capital jury selection in the Florida county has found.

The study, Racialized Impacts of Death Disqualification in Duval County, Florida, conducted by University of Central Florida criminal justice professor Dr. Jacinta M. Gau, was the centerpiece of a challenge to the county’s capital-case jury selection practices brought by lawyers for the ACLU on behalf of Dennis Glover (pictured, center) in his capital resentencing trial. Glover was unconstitutionally sentenced to death by a Duval County judge in 2015 following a non-unanimous sentencing recommendation by his jury. On October 21, 2022, State Attorney Melissa Nelson withdrew the death penalty from Glover’s case, avoiding a hearing on the jury issue, and the court resentenced Glover to life without parole.

Dr. Gau reviewed transcripts and other materials relating to 1,042 prospective jurors called for jury duty in the 12 capital cases tried in Duval County (Jacksonville) from 2010 through 2018 to determine the extent to which the combination of death-qualification and discretionary jury strikes affected the composition of death penalty juries in the county. She found that the practice of “death qualification” — the removal of potential jurors from service in a capital case because of their expressed opposition to the death penalty — “disproportionately excluded people of color, and Black people … in particular.” The prosecution’s exercise of discretionary strikes “also exclude a sizeable percentage of Black venire persons,” Gau found, with Black women again the group most likely to be excluded, followed closely by Black men.

Discriminatory jury selection was just one of several major issues presented in Glover’s case. He has consistently maintained his innocence in the murder of his neighbor, Sandra Allen. His lawyers say that school records and IQ tests demonstrate that he is intellectually disabled and therefore should never have been eligible for a death sentence. His 2015 death sentence was imposed after a 10 – 2 jury recommendation, but it was overturned in 2017 after the U.S. Supreme Court struck down Florida’s sentencing scheme. For five years, Nelson rejected Glover’s requests to waive the death penalty, insisting that she would only do so if he admitted his guilt.

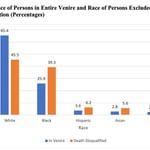

Gau’s study found that the death qualification process removed jurors of color at significantly higher rates than white jurors. 33.8% of Black potential jurors were excluded by death qualification, along with 38.0% of other jurors of color, while only 15.5% of white jurors were excluded. While Black jurors comprised 25.9% of the general venire, they constituted 39.3% of those disqualified because of their views against the death penalty. Likewise, other jurors of color (Latinx, Asian, or other race) comprised 8.9% of the overall jury pool, they constituted 15.2% of those disqualified because of opposition to capital punishment. By contrast, white jurors comprised 65.4% of the entire venire, but only 45.5% of death-qualification strikes.

When death-disqualified jurors were analyzed to exclude those jurors whose answers to jury selection questions revealed other legitimate bases to strike them, the racial disparities became even broader. “Approximately 39% of Black venire persons who are ready, willing, and able to serve are banned from doing so by the death-disqualification rule,” Gau found. “ A full 43% of people of other races (Hispanic, Asian, and so forth) are barred from service by the rule. This sits in contrast to only 17% of White venire persons for whom death-penalty opposition poses a barrier to jury service.”

The combination of death qualification and prosecution discretionary strikes even more disproportionately disenfranchised Black jurors and was particularly discriminatory against Black women. “[F]ully two thirds of Black women otherwise eligible, qualified, and willing to serve were excluded by the combination of death qualification and prosecutor peremptory strikes, as were 55% of Black men,” Gau wrote.

The racial disproportionality of the exclusions of Black jurors is magnified even further in the jury room because African Americans are already a minority voice — representing about 30% of Duval County’s population — and are already underrepresented in the pool of potential jurors. Gau found that African Americans comprised 25.9% of the general venire but 22.6% of those selected to serve as jurors or alternate jurors. The representation of other jurors of color fell from 8.9% to 6.4%. White jurors, on the other hand, moved from 65.3% of the general venire to 70.9% of those ultimately empaneled.

Gau’s results are similar to those in a recent study of death qualification in North Carolina. Researchers from Michigan State University studied jury selection in Wake County (Raleigh) from 2008 to 2019. The researchers found statistically significant evidence of racial disparities in death qualification, with Black potential jurors removed “at 2.16 times the rate of their white counterparts.” That research was submitted as part of a challenge to death qualification on behalf of Brandon Xavier Hill, who is facing capital charges in Wake County.

Studies have shown that more diverse juries render more accurate verdicts. Until 2016, Florida’s capital sentencing system permitted judges to impose death sentences based up non-unanimous jury votes for death, further diluting — and in some cases silencing — minority viewpoints. Thirty people in Florida — by far the most in the nation — have been exonerated since 1973 after having been wrongfully convicted and sentenced to death, one exoneration for every 3.3 people put to death in the state. Of the 24 exonerations for which the jury vote is known, 22 (91.7%) involved judicial decisions to override jury votes for life or nonunanimous jury recommendations for death.

Dr. Jacinta M. Gau, Racialized Impacts of Death Disqualification in Duval County, Florida, Expert Report in State v. Glover; Elizabeth Weill-Greenberg, HIS ATTORNEYS SAY HE’S INTELLECTUALLY DISABLED. A ‘REFORM’ PROSECUTOR WANTS THE DEATH PENALTY, The Appeal, January 22, 2022; Jacksonville man convicted of murder of former neighbor resentenced to life in prison, First Coast News, October 21, 2022

Innocence

Nov 20, 2024